THE WILD BEAST

An exegesis by Flore Vallery-Radot

“A man (sic) without ethics is a wild beast loosed upon this world.”

“A man (sic) without ethics is a wild beast loosed upon this world.”

One day I found myself covered in blood, in excruciating pain. I was terrified. I thought someone had stabbed me or maybe I was dying of a terrible disease… I was 14. It was actually a very normal day - one that most women* will experience in their lifetime; their first period. My mum had not explained anything about puberty and menstruation.

Fast forward 20-years, when I began my career as a filmmaker with several film projects. I first launched a monthly artists’ barter system: a mini film in return for a work of art. Then I launched a self-inflicted 30-day, 30-film challenge where I filmed an artist in the morning and edited their cinematic portrait in the afternoon. During that time, I met with more than 200 creatives, mostly women. I spent hours and sometimes days with them, hovering around their work, trying to capture the essence of their gestures. This unique dance of the camera created a special bond which allowed for open discussions. Often, the subject of the female body was evoked. I told them my story of menarche, the first day of my period, and all the women I shared it with told me similar stories. I discovered, horrified, that this is a largely shared experience even in the mostly privileged world I was filming in. A study in the UK revealed that 44% of girls do not know what is happening to them on the first day of their period (Pasha-Robinson, 2017).

Beyond menarche, all key changes to the female body were seen by the participants of my films to be taboo, challenging at the best of times or even traumatic. This includes pregnancy, abortion, miscarriage, birth, female health issues and menopause.

When I decided to apply to film school my goal was to steer away from the purely poetic and aesthetic approach of my mini-films and use newly acquired skills to impact social change. I was yearning to film themes that are close to my heart but still heavily taboo. My hope was that I could affect social change through “using creative media as a tool for breaking taboo” (Steen, 2019). Menstruation felt like a good place to start.

“Only morality in our actions can give beauty and dignity to life.”

I began my Capstone project with the intention of making the most inclusive film possible. Heavily interview-based, it would have attempted to tell menstruation stories of a vast array of participants from different cultures, ages, genders, sexual orientations, abilities, and professions. The more I tried to make the film closer to my experience, true to my story, the more I thought of making it from the point of view of one person. Someone who would, at the time of the shoot, worry about the first day of their period. My 10-year-old daughter Leonore seemed the ideal candidate. She had not yet had her period and had lots of questions. My method of explaining puberty to her siblings Nilou (19) and Alex (17) was not ideal; it was not my mother’s silence, but it was not much better. My Capstone film therefore became my way of having this important conversation with my daughter.

Throughout my career as a photographer and filmmaker, I have been regularly confronted with ethical questions, both from my participants and from myself. I was noticing a gross imbalance of power between me, armed with my camera, lights and the proverbial editing scissors, and the participants of my films. I was also asking myself, “is filming that or cutting this out OK or not OK?” The idea of making my daughter the main participant of my film made these questions even more urgent. How can I obtain informed consent from a 10-year-old? I'm her mother, so of course she will say yes to what I ask, but will she understand what the film is about, what impact will it have on her life? I also wondered if explaining too much, demanding that she understood everything about the film would impair the candour demanded by observational documentary. From these concerns, my research question arose:

How can documentarians ethically create films with their children without compromising spontaneity?

The first part of this exegesis describes my chosen methodology and methods. Then, I have divided the work in three chapters. In Chapter one, I outline ethical theories established by ancient and modern philosophers, psychologists, and screen scholars. I then list all the ethical considerations I could find in the work of documentary film scholars and practitioners such as Kate Nash, Bill Nichols, and Gordon Quinn. This analysis led me to discover the lack of research in the field of documentary that specifically focuses on making films with one’s children.

In Chapter two, drawing on the work of documentarians Rebecca Barry and Maya Newell, as well as mental health professional, intimacy coordinator and consent specialist Michela Carattini, I attempt to create a list of tools and processes to navigate ethical issues in documentaries. Through looking closely at the approaches of filmmakers Barry and Newell, I seek to understand what ethical questions arose during their filmmaking processes and how they responded to them. In Chapter three, I describe how I implemented these tools and processes into the making of my film First Blood [working title]. Finally, I conclude this exegesis by listing three recommendations which, in my opinion, could make the life of documentarians easier and allow them to create more ethical films.

Albert Camus's often quoted statement “A man (sic) without ethics is a wild beast loosed upon this world” (Devega & Woodley, 2008, p.2) inspired the name of this exegesis. I do not want to be this wild beast to anyone and certainly not my own daughter. This exegesis is a first step to become better than that wild beast.

This exegesis is presented in a linear way.

Please scroll down to read.

Or jump to the chapters via the top menu “EXEGESIS”.

DOCUMENTARY - ETHICS - CHILDREN - POWER - CONSENT - RESPECT - TABOO - PROTOCOL

This exegesis takes a constructionist approach. It considers that truth is constructed by our human minds as we give our insider’s perspective on what is occurring. Meaning “is contingent upon human practices, being constructed in and out of interaction between human beings and their world” (Crotty, 1998, p.42). My interactions with the participants of my documentary, the film crew, and the film practitioners I have met will inform this research.

My methodology is defined as creative practice or practice-led research where I will be “systematically gathering reflections, [ideas and research] on the process of doing/making, in order to contribute knowledge to the practice of doing/making” (Batty & Kerringan, 2018, p.7) my documentary film, First Blood [working title].

I have used several methods to gather information and reflections in the process of making First Blood [working title] including: the creation of formalised documentation in the form of an ethical protocol for filmmakers (see Appendix 2) developed in consultation with mental health professional, intimacy coordinator and consent specialist Michela Carattini; interviews with film practitioners Rebecca Barry, Aslaug Holm, Maya Newell and the film’s main participant Leonore; and finally, a critical reflection through a mind map, reflections from my personal journal, and correspondence between Michela Carattini and my film school teachers. A textual analysis on documentary ethics has also been completed covering past and current academic research in the domain.

The combination of creating the film and researching for this exegesis has allowed me to follow the classic Kolb Learning Cycle (Schon, 1987). It is the idea that we learn from an experience such as making a film, then reflecting on what went well and what did not. The next step is to make generalisations about these findings. The last step is to use my conclusions or test them on future projects.

I have used the three types of reflections described in the Reflective Practitioner Approach (Schon, 1987). I started with reflection-in-action, which is reflecting in the moment, as I was doing. This applied to when I was filming or while in the edit suite. Then I practiced reflection-on-action which is reflecting after the event. I critically analysed what happened and what I had learned after the shoot, and while starting the editing process. Lastly, I did reflection-for-action (Cowan, 1998) which is reflecting on what I have learned in order to improve my future practice. It’s reflecting on this project to move into the next with better knowledge and tools.

In this first chapter I will explore, outline, and analyse ethical considerations within the context of documentary filmmaking. I will be analysing these considerations through the making of the documentary First Blood [working title] based on my daughter Leonore’s transition into puberty.

For the purpose of this exegesis, I will use John Grierson’s definition of documentary: “the creative treatment of actuality” (Grierson, 1933, pp. 7–9). This slippery definition remains unimproved upon, though the debate continues to rage among documentary filmmakers and critics about how much license should be extended to the ‘creative’ aspect of that definition, and what constitutes ‘actuality’ (Eitzen, 1995). This definition also draws attention to the ethically murky terrain that documentary filmmakers work in when it comes to representing (or misrepresenting) their subjects.

At the start of my journey making First Blood [working title], I needed to understand what the term ‘ethics’ means and how it has evolved over time, in order to apply it to my process.

The term ethics refers to the philosophical study of right and wrong (Mackie, 1990). According to Plato, a man “has only one thing to consider in performing any action — that is, whether he is acting right or wrongly, like a good man or a bad one.” (Tredennick, 1961). Later philosophers such as David Hume and Immanuel Kant reflected on the systems put in place to reinforce ethical conducts. Two different approaches were identified: the deontological approach which defines if an action is good or bad in itself; and the teleological approach which is concerned with the consequences of the action (Entrican Wilson & Denis, 2022).

Documentarians have so far rejected any rigid ethical protocol or deontological code of practice arguing that their practice is an art and that each situation, each film project, is too different from the other and cannot be ruled by a one-size-fits-all code of ethics (Barry, 2021). “Many documentarians resist the idea that they are journalists or should hew to a journalistic standard of behaviour” (Aufderheide, 2012, p.365). Aufderheide explains that even if there is a common ground between the work of a journalist and a documentarian, their approach, processes, and delivery are not the same.

Without a code of ethics, how far can we go? Documentary ethics scholar Calvin Pryluck asks: “What is the boundary between society’s right to know and the individual’s right to be free of humiliation, shame and indignity?” (1976, p.21). Can we consider the public’s right to know a higher good worth all actions necessary to make an informative film? These are the questions documentary filmmakers must consider every time they start a new project.

Finally, after reading documentarian Rebecca Barry’s thesis The Dark Grey Zone (2021) and interviewing her, I was inspired by her statement: “In much contemporary documentary practice, ethical issues—particularly that of informed consent—fall into a dark grey zone” (2021, p.2). It pushed me to list what ethical concerns I had prior to making my film, the concepts at the core of documentary ethics and more importantly to my practice: what could go very wrong.

The very actions that constitute the making of a film alter the participants’ reality and their story. The filmmaker, armed with a camera, lights, microphones and sometimes accompanied by a crew, intrinsically creates an imbalance of power toward the participants of a documentary. Even before the framing of a scene, the act of writing the script enables the filmmaker’s preconceived ideas to drive the story. The editing process allows filmmakers to re-create sentences and construct the story they want to tell. The filmmaker controls the narrative.

The power over story held by the documentarian impairs the possibility of informed consent (Nash, 2012). The persons being filmed cannot have an exact notion of how their reality will be represented, and sometimes someone consenting to be part of a documentary film does not mean they actually do (Quinn, 2016). Pryluck also discusses the risk of coercive consent in documentary: “With the best intentions in the world, filmmakers can only guess how the scenes they use will affect the lives of the people they have photographed; even a seemingly innocuous image may have meaning for the people involved that is obscure to the filmmaker” (Pryluck, 1976, p.23).

It is even more the case for vulnerable participants. In my film, the main participant is a little girl, who is also my daughter. She is vulnerable because she has been taught to say “yes” to adults and to obey her parents. She trusts her mother to make the right choices. This is also true for the members of my family and Leonore’s friends who have taken part in the film. They have first and foremost agreed to participate to please me and because they trust me. How do I know if I am not in fact forcing them?

An important aspect of power balance is age. There is an obvious age gap between my daughter and I. At 11, Leonore cannot understand what talking about puberty on screen might lead to. She does not fully grasp the impact of having her image on screen, the potential mockeries she might be the target of. She cannot truly comprehend the everlasting accessibility to her image, available forever for anyone to see. Her words could be misinterpreted by viewers, or she could look back in a few years and be embarrassed.

When I interviewed Rebecca Barry on consent, she tried to put herself in my daughter’s shoes: “How am I going to feel about this when I'm 20 [] when I've left university? I'm going for my first job as a serious lawyer and here I am talking about periods.” (Barry, i/v, 2022).

Yet the classic concept of power in documentary as described in this paragraph can be challenged as has been done by Kate Nash using a Foucauldian approach (Foucault, 1983). Foucault suggests that there is no such thing as two distinct groups: the powerful and the oppressed; but more so a “complex strategy spread throughout social systems” (Nash, 2010, p.27). Documentary participants are free to engage in acts of resistance (Foucault, 1983, p.209). They can refuse to be filmed by leaving the set or in more subtle ways like Lyn Rule in Tom Zubrycki’s film Molly and Mobarak (2004) putting music on or by swearing. Rule hopes Zubrycki will stop filming.

If Leonore wanted to stop the film to be made, she could have done so and still can; but as all documentary participants, she has her own motivations to take part in the film. She feels valued to work on a project with a team of adults. It is this freedom, and the power to stop it all, which re-balances the power dynamics in documentary filmmaking.

Maybe one of the keys is the concept of fair exchange. If both participant and filmmaker feel that they are gaining something from making a film, it becomes a win-win situation. “It is a fair exchange”, according to Zubrycki, “if the filmmaker and participant both stand to gain something from the documentary encounter” (Nash, 2009, p.18). I am hoping that Leonore has as much to gain as I have: spending more time with her mother, gaining agency, having a creative input, and more importantly getting on the pathway of puberty with a lot of knowledge, less shame than me at her age and an on-going open discussion.

After measuring the risks inherent to the imbalance of power in documentary filmmaking, one very important responsibility held by documentarians is honesty. It is a presupposed condition to deserve and respect the participants’ trust. "Trust is central to (observational) documentary with the filmmaker and participant entrusting each other with things that they value" (Nash, 2012, p.8).

If filmmakers proceed to mine information, exploit participants’ reactions, image, and voice, without informing them of their true intention, their honesty is compromised, and trust cannot be acquired. Transparency is the first step of an honest collaboration. Before starting to shoot any scene in my film, I made sure that all participants and their parents (if they were minors) had a very precise idea of my intent.

Filmmakers also place trust in their participants. They trust that the people they have chosen to represent a story on screen will tell the truth, give them access to the necessary information, fully collaborate, and remain committed for the duration of the whole filmmaking process. Their commitment is sometimes required for a long period of time. It can require their presence long after the film has been shot; for example during the film’s promotional campaign, or even during an impact campaign.

The conflict at the centre of documentary ethics is between participants’ legal and moral rights to privacy and free speech or the right to inform (Nash, 2012). Does the informative value of documentary allow filmmakers to expose participants’ lives or even sometimes violate their privacy? Is the greater good of bringing to light a societal issue like the taboo of puberty and menstruation or wanting the improve the life of girls, an argument strong enough to expose my daughter’s private moments? It’s a question I have asked myself repeatedly and that I have discussed with her. We have concluded together that helping girls who will watch the film feel better about their body growing up, helping parents have more open dialogue with their growing children, and helping boys be part of the discussion will be worth the intrusion.

It’s also important to note that the right to privacy is not always a simple yes or no. A participant can allow partial display of their image or their story and decide to hide other parts.

The right to privacy is the right to decide how much, to whom, and when disclosure about one’s self are to be made. There are some topics that one discusses with confidants; other thoughts are not disclosed to anyone; finally, there are those private things that one is unwilling to consider even in the most private moments (Pryluck, 1976, p24).

A series of incidents at Leonore’s school which involved a group of boys repeatedly bullying her and a few of her friends, led one of our film’s participants to withdraw her consent. This little girl, aged 11, became suddenly aware that those boys might watch her talk about hairy armpits, body odours, and bloody underwear. Her mother demanded her privacy to be preserved (see Appendix 3) which I accepted without question. The rushes where she appeared were not included in the cuts.

Coming to a documentary film project with a strong sense of respect seems obvious. In my personal experience, it means to try, as a filmmaker, to put myself in the position of the person I want to involve in the film: participant, or crew. This means to be vigilant and examine each action involving a participant from their perspective, as if it was me sitting under the lights. Would this action or question make me comfortable or not? If not, can it still be in the film if we talk about it? It is an entirely subjective approach, but it has helped me be more respectful in my process.

Norwegian documentarian Aslaug Holm filmed her two sons from early childhood to late teenagerhood in her documentary film Brothers (2015). As a viewer you can sense her great respect for her children. It is shown in the choice of images, or when she presses stop recording as soon as they ask her to.

Respect could also mean that filmmakers are appreciative of the time and involvement of the main participants in their film. To thank them, they can decide to pay them or share equity of the film. Documentarian Maya Newell came to AFTRS** to do a Masterclass on her film In My Blood It Runs (2019). She explained how she formalised her collaboration with the First Nations community with whom the film was made and how she shares the film’s equity with the participants.

As documentarians we have a role to play in telling stories that can change the status quo for a better world. We can use our craft to critically explore the political arena, social issues, or our world’s power dynamics. But Maya Newell’s approach raises the questions: who has the right to tell this story? What biases are we bringing to the story we want to tell? Can our biases and the imposition of our culture lead to indoctrination?

Disparities between filmmaker and participants in terms of cultural background, gender, sexual orientation, age, political or religious opinions, often lead to misrepresentation. Nash wonders "[t]o what extent does the documentary reduce the participant to a stereotypical role, dictated in advance by the filmmaker?”

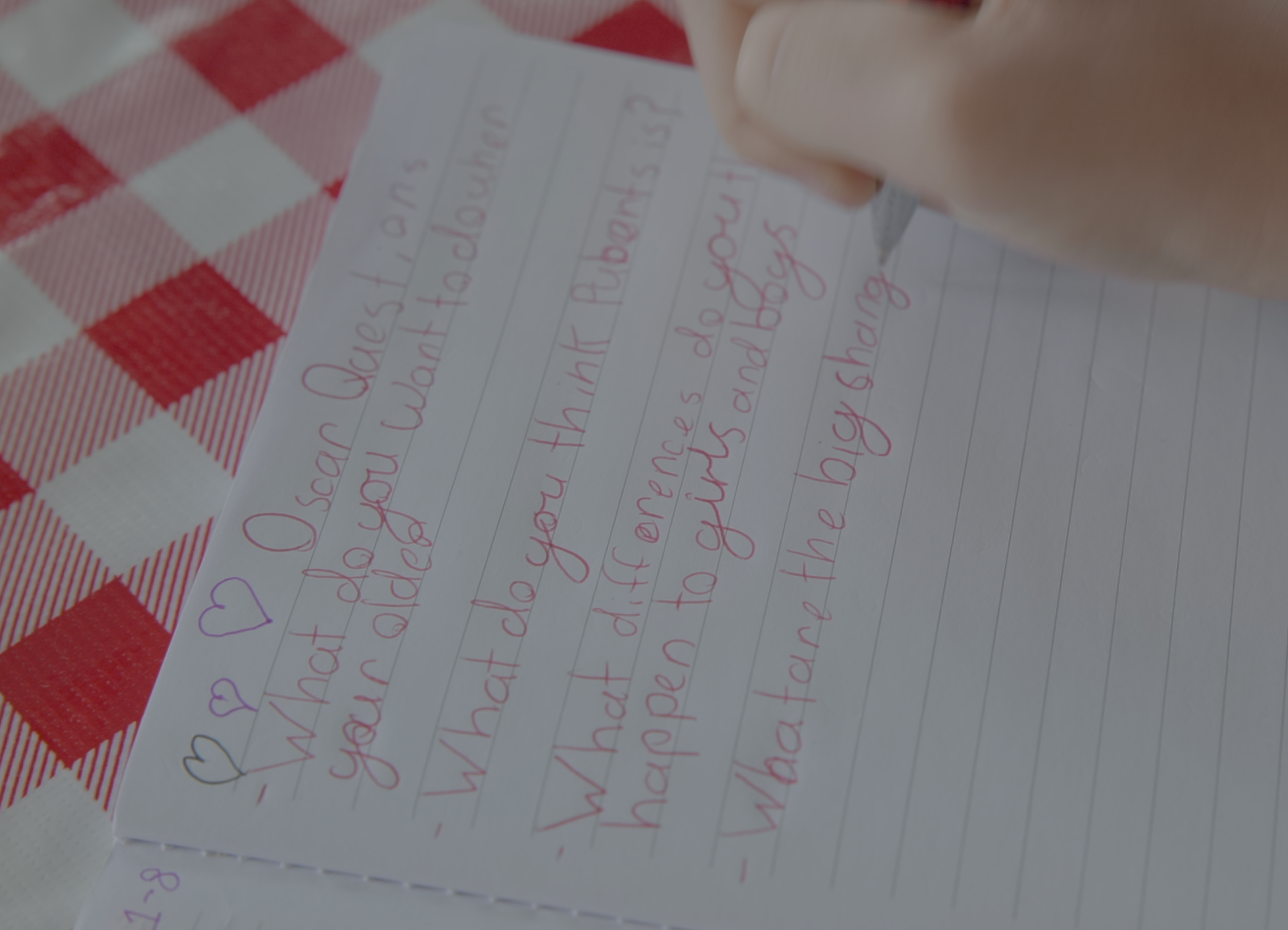

I am making First Blood [working title] through the lens of a 46-year-old woman who cannot unknow what she knows about puberty and the adult female body. The risk to consider is the misrepresentation of Leonore’s world and story; or worse, to make her the actress of my mockumentary. I have found tools to minimise these risks including, among other things documented in the following chapters: letting her ask the questions during our dialogues, choose the interview questions to the other participants, and let her film her side of the story with her own camera.

For the mother that I am, one important ethical consideration is the duty of care I owe my daughter, who is the main participant in my film First Blood [working title] but also the rest of my family. I need to make sure that they feel safe while telling their story or simply being present in the film. I need to be able to shut down the camera when they want me to and cuddle Leonore or reassure her when things are getting emotional. I feel the need to do that even if it sometimes means not getting the image I wanted.

My own sense of care was illuminated while watching Herz Frank’s Ten Minutes Older (1978) which shows a row of young children filmed from the point of few of the puppets in a puppet show. The camera focuses on a little boy. His face takes all the screen. His features are altered by his reactions to the story unfolding. Moments of sheer horror bring tears to his eyes and his little hand reaches for his open mouth. Witnessing such distress was unbearable to me. As a filmmaker, I would have intervened and probably ruined the film.

Filmmaker Agnes Varda said in an interview that using her children in her films was “actually a rather dishonest move that all filmmakers make, to cast their children and not ask their opinion.” She said about her son Mathieu: “I had filmed him without asking him. It’s not even asking his permission. I probably said, “Do you want to be in this film?” When you’re nine, I don’t think you have the authority to say no” (Marchini Camia, 2019). Learning from Varda, I want to make sure that my children Leonore (11), Alex (17) and Nilou (19), my nephew Oscar (11) and any children involved in my film are getting the respect and care they deserve. It is at the heart of this exegesis.

“If a director is not willing to accept a no, then she or he is not seeking consent.”

In this chapter, I outline the ethical tools and processes discovered during my two years studying at AFTRS and while making my capstone film First Blood [working title], addressing the ethical considerations outlined in the previous chapter. I have drawn precious information and insight from the experience of professional practitioners who have taught masterclasses at AFTRS such as documentarian Maya Newell; and from professionals I have interviewed including documentarian and producer Rebecca Barry, and intimacy coordinator and consent specialist Michela Carattini.

My first encounter with a filmmaking framework involving protocols and guidelines was during Maya Newell’s masterclass. Inspired and guided by Screen Australia’s Indigenous Pathways and Protocols, Canada’s On screen protocols and pathways, and the Journalist Code of Ethics, Newell put in place a formalised collaboration and partnership with the participants of her film In My Blood It Runs (2019), their family and their First Nations community.

Newell’s framework contained creative and robust consultation techniques at all stages of the filmmaking process. Her main goals were to tell an authentic story, give agency to the participants, and obtain their informed consent. Newell had a long-term connection with the community prior to making the film but is not Indigenous herself. It was therefore important to her, to minimise misrepresentation, to ensure cultural safety, and to develop an ethical framework.

First, she created a film committee constituted of members of the community, a team of advisors including William Tilmouth, an Arrernte elder and film advisor, and participants’ family members who teamed up with her crew. Together they workshopped ideas. This rigorous consultation process allowed the story to come from the community and the family of ten-year-old Dujuan Hoosan who, at the time of filming, was struggling to balance his traditional Arrernte/Garrwa upbringing with the state educational system.

Conscious of the power dynamics between her and her participants, she allowed them to film her as a way to offer them shared authorship of their story. She also had ‘open-door policy’ during post-production, inviting participants to watch cuts and give their feedback. Additionally, Newell stipulated that any profits generated by the film should be shared with those represented and she remains in touch with them and their families.

Through these processes and her prior long-term involvement with the Arrernte community, Newell maximised the chances gaining informed consent from the participants and their family. “This has been a deep and ongoing process to ensure that each individual comprehensively understands the terms of involvement and the control they have over how their stories and images [are] portrayed.” (In My Blood It Runs, 2022)

Finally, the film launch was accompanied by an impact campaign managed by impact producers Alex Kelly, Lisa Sherrard, and Georgia Quinn. The goals of the campaign were education, juvenile justice, and racism. It encouraged the viewers to take action by: signing the petition “Support Aboriginal kids' right to education in First Language and Culture”, donate to an Arrernte-led school on Dujuan’s homeland, donate and take the pledge to support the campaign to #LearnOurTruth about history of colonisation in Australian schools.

Inspired by Newell’s approach, I decided to establish my own protocol for First Blood [working title]. I felt the need to define the terms of engagement between my participants, their parents, my crew, and myself. I also wanted the protocols to ensure adequate care for everyone involved. The simple idea was that we all deserve the respect, fair representation, and treatment.

Looking at all the material that I had, the long list of potential ethical risks to minimise, and the immensity of the resulting protocol building, I felt that I needed to enlist a professional who could offer me personalised advice and support, so I called Michela Carattini. I will discuss her involvement in First Blood [working title] in the following paragraph.

The first film I directed at AFTRS was a short called Landscape (see Appendix 6). The idea was to fly over the skin of different women like you would over a landscape, admiring its cracks, folds and stretches; observing the results of life and the body’s tectonics. The film interrogates the different treatments a skin and the earth’s crust receive. The first being often the object of shame, the latter worthy of admiration and artistic depiction.

I organised a casting of six women with different skins tones and body types. I required that they have a scar or stretched marks somewhere they could show on camera. I spent an hour on the phone with each of them to discuss what they felt comfortable showing or not.

Late in the process, the production department of the school required consultation with an intimacy coordinator prior to production being approved. My reaction was very negative. I felt that a person I did not know was interfering with my special participant-director relationship. I felt as if someone was asking the participants: “Are you really sure you’re OK to be part of this film?” making me look like the bad director who did not execute the consent process properly.

The night before the shoot, Michela Carattini called me on the phone. I warned her that I was not happy with her fiddling with my film process. There was a big smile in her voice and within two sentences she had convinced me that she could be useful. She offered advice that proved indeed very precious. She recommended that I set up a walled marquee directly on set instead of making our models walk in robe between the AFTRS change rooms and the set. Two paths, in and out of the studio, were created for privacy. The women were called by Michela to formalise their consent.

Everything went smoothly until it was the moment to film. Five out of six participants had difficult stories: accidents, life altering medical conditions, mental health problems. Suddenly, I felt unprepared to take in their story and their emotions. I came to this shoot naive, thinking participants would come with stretch marks, a glass cut or an old surgery scar.

One of the women asked me for lunch. As we sat down to eat, she shared the story of her rape as a child and a lifetime of domestic violence and abuse. I did not manage to compartmentalise her story and mine. I was a mess and very embarrassed to go back on set, but more importantly feeling extremely guilty to have retraumatised someone by asking her to be part of my film.

Back home, I called Michela Carattini who helped me enormously by talking through my responsibilities as a documentary director and discussing the role of empathy in that position. At the end of the conversation, I mentioned my next project First Blood [working title]. I asked her if she would be interested in being a consultant on the film and she accepted. More on that collaboration and how an idea was born from it in the next chapter.

While reading on documentary ethics and talking to other filmmakers about it, I discovered new tools. In her thesis the Dark Grey Zone (2021, p.127), Rebecca Barry mentions Ethi-Call, a service run by the not-for-profit organisation that operates in Sydney. Their staff helped me identify potential ethical dilemmas and test them through the prisms of religion, culture, and family values.

Also through the work of Rebecca Barry (2021), I discovered The Ethics Lab an international organisation founded by Dan Geva “committed to creating a universally tailored pedagogy on ethics, one that is specifically sculpted to address the needs of film students, teachers, and scholars” (The Ethics Lab, 2022).

While Barry was working on her documentary I am a Girl (2013), she established an “ethical safe zone” (Aufderheide, 2009, p. 21), an anonymous online hub where filmmakers could submit their ethical dilemmas and discuss them with the documentary community. She also recommends that documentary festivals offer an ethical forum where questions could be asked to a panel of filmmakers and scholars.

Another ethical tool has been generated and tested by filmmaker Jean Rouch and anthropologist and researcher Edgard Morin in their pioneering documentary of Chronique d'un été (1961). Nearing the end of the documentary making process, the filmmakers recorded a discussion with their participants after they had watched a projection of the first cut (Bitoun, 2012). The idea was to reflexively show the mechanics of filmmaking to the participants and the audience. With this open conversation, the filmmakers offered a sense of agency back to the participants who were able to comment on any misrepresentations at the hand of the filmmakers. This feedback illuminated the role of directors in shaping or manipulating the ‘truth’.

These discoveries inspired me to experiment during the entire process of making First Blood [working title]. In the next chapter, I describe the tools I used, what worked and what did not.

“Documentary filmmaking is a never-ending exploration of your own values, as they are buffeted by the realities of getting work done. But the end product will be measured by its integrity, and that depends on our keeping the ethical questions front and center. Which doesn’t mean we always get it right.”

In the following paragraphs I describe my initial ideas and the steps I took to implement them, including what helped and what did not. This process led me to imagine strategies for an ethically strong future filmmaking practice. I will present these ideas in the shape of recommendations in my conclusion.

The first tool I should mention is the mind map, a concept mapping technique which helps identify potentially difficult themes and ethically complex elements. It has been a way for me to make sure that all possible themes related to an eleven-year-old girl’s entry into puberty were available for me to see and study. As I feel a sense of accountability to my children and the film’s viewers, I wanted to be as thorough as possible to avoid any blind spots.

I wrote main themes in big capital letters such as TABOO, PRACTICAL, BIOLOGY, and then sub-themes for example in surrounded the word BIOLOGY by Cycles, Uterus, Puberty, Vulva, Blood, Books. I built clouds of keywords around these sub-themes. For example, around Blood I noted: Irregular, Flow, Smell, Texture, Colour. I then used the platform Canva to make it more visually efficient.

Reading specialised books for children such as Welcome to Your Boobs (Stynes & Kang, 2022) or Guide to Growing up (Nuchi, 2017) helped me fill the gaps. I took notes of the discussions I had with peers, friends, or teachers who shared their stories of menarche.

Once I felt that the mind map contained all the subjects I wanted to explore in the film, I started to create a beat sheet which included these elements. Through this rigorous process, I felt confident in my accountability to the participants in my film and that I was across any potential ethical issues that could arise in the filmmaking process.

The biggest ethical consideration was gaining my daughter’s informed consent. After working with Michela Carattini on my previous film (see Chapter 2), I thought she would the perfect “person in the middle”. I listed the services that I needed from her: an initial check-in with Leonore alone; a first consultation with me to help draft a protocol; followed by a second one to review the protocol’s changes; and finally a follow-up with Leonore when the film is finished. She offered to be available for Leonore to contact if she had concerns or for advocacy via email or WhatsApp, and provide production documentation on risk mitigation strategies.

Before describing the work, conflicts and resolutions that happened during my collaboration with Michela, it is important to note that I personally encountered a strong culture of resistance against intimacy coordinators. I heard people from within the industry and even my educational institution argue that these professionals were a threat to spontaneity, particularly in documentary. Some claimed that they only have the interest of the participants at heart and not the director’s. It worried me but Michela soon put my doubts at ease.

Michela’s consultation with Leonore took place on Zoom after school and lasted for an hour. I trusted Michela to talk to Leonore alone because she is a trained psychologist. Leonore came out very inspired and she became much more interested and involved in the process.

During my first consultation, Michela and I discussed my draft of a protocol. I was excited to benefit from her expertise in consent and respectful practices from the world of on-screen drama. She explained that her speciality is “de-roling”, meaning to bookend participation in a film by putting in place a closure practice through rituals. It’s an ancient and evidenced-based strategy to minimise secondary traumatisation in storytelling. In cinema, it helps actors get in and out of a role. She suggested that Leonore start singing a song at the beginning of each filming session and another at the end, when the camera was switched off. It seemed a strange idea to me, and potentially a very disruptive one, so Michela suggested to light a candle instead, or hang an object on the wall. As we have no wall hooks, Leonore and I went to buy a special film candle and for the next few days we either forgot to light it up or to blow it out.

During my second consultation with Michela, I explained that actors’ rituals could not work in observational documentary because they put spontaneity at risk. The key to this style of documentary is to show Leonore and I as real people having real discussions about subjects that are hard to talk about in our culture. Doing anything else other than casually and very regularly grabbing the camera from the kitchen bench would prep Leonore too much. It took time for her to stop “acting” in front of the camera and simply be herself. But Michela insisted that we needed to bookend Leonore’s participation in the film somehow. After some disagreements, we settled on a proclamation at the beginning and at the end of the filming process as a whole. We agreed that it would work much better, be less invasive, but be still efficient as it would indicate to Leonore that during that period, filming could happen at any time, unless she said no. We made it a celebration. I filmed a proclamation of the start of the film and I will do the same at the end.

After the consultations and the work on the protocol, the question “is Leonore too prepared?” kept raising up. Instead of the shy little girl of “before the film”, she grew into a pro-interviewer. All along the process she became less timid. Asking questions she was first mortified to even hint at, became second nature. Interestingly, there is a parallel path between learning about the changes occurring in her body and mind, and becoming knowledgeable in documentary processes. She seemed empowered by her newly acquired knowledge. She ended up writing interview questions herself, as well as setting up microphones and checking sound for each session.

One unexpected consequence of working with Michela and creating a protocol together was the beautiful improvement of my relationship with my daughter Leonore. Our honest discussions about consent made her realise that I value her opinion, respect her consent, and go to a lot of trouble to ensure her wellbeing. It has created a relationship of mutual respect and trust. If anything, it will be the greatest achievement of this film.

My first step was to write down the ethical concerns I had and which I mentioned in chapter 1. The second step was to listen to Maya Newell and the teachers at film school who taught a Documentary Ethics class. I listed the ideas shared and added my own. An interesting exercise was to use the Screen Australia Pathways and Protocols’ summary checklist (Janke, 2009, pp. 24-25) and replace the words “Indigenous” or “Indigenous people” with “the participant” or by “Leonore”.

To construct the protocol (see Appendix 2), I created a section for each group of people it was targeting: Leonore and I, the production team, the other participants: adults and children as well as their parents or guardians, and the viewers of the film.

For Leonore and I, the goal was to give Leonore agency by offering her the right of veto throughout the entire filmmaking process. This is not recommended in documentary filmmaking, and I have been told at school that funding bodies might not finance a project with this in place because of the high risk of the film losing its main protagonist. The reason why it was important for me to implement it is because I believe that unless I am open to a “no” I am not fully seeking consent (Carattini, i/v, 2022).

Another important element was giving Leonore access to Michela for additional advocacy or support, making her the co-director of the film and letting her manage the interviews, the set-ups within the house, and giving her a camera or a phone to film her point of view. The other main goal was to protect her world. We put in place the closure practice noted in the paragraph above, made sure she was notified of any heavy filming or visits to the film school twenty-four hour in advance. We limited filming time to a maximum of four hours per day and five days per week. In the state of New South Wales, The Office of the Children’s Guardian regulates the way organisations uphold children’s right to be safe. Michela raised her concerns that although fiction film productions must abide by strict rules when employing children, documentarians don’t. Children can work a limited number of hours per day and days in a week. “Children in documentaries are completely at the whim of their legal guardian and the filmmaker” (Carattini, i/v, 2022).

Michela and I also gave her a list of expectations: to give the film her best go and understand that making it requires effort. My obligation was to inform her to the best of my knowledge of the themes of the film as well as the risk of being in one.

Lastly, I was inspired by Newell’s shared equity system she set-up for her documentary In My Blood It Runs (2019). If Leonore was an actress, she would have been paid for the hours spent in front of my camera. I decided to share half of any revenue generated by the film with her on a bank account to her name which she will be able to access on the day she turns 18 years old.

For the other participants and their parents, I felt the same responsibility as for Leonore. Because their presence in the film will be less prominent, they have not been given a camera, co-directing roles, or equity, but they did get the same veto rights. My main concern was to gain informed consent from them and their parents or guardians. No matter their age, it was critical for me to respect their “no”. I therefore put in place consent meetings: one meeting before starting to shoot (with their parents or guardian) and a second one inviting them to watch the rushes before signing the release form. This has proven to be very difficult to organise. Parents lead busy lives and sitting down with me for twenty minutes initially and an hour for the rushes’ review seemed a long time. The parents who insisted on signing the release form without the second meetings ended up being the ones asking for their daughter to be taken out of the film. The parents who accepted the process loved discovering what their child had to say about growing up.

For the crew, the goal was to give each member an opportunity to reach out if they felt triggered by the themes of the film or uncomfortable with our process. We gave them access to Michela and the school’s counsellor. We asked that they behave respectfully and as discreetly as possible in front of the participants on set or in the edit suite.

Later on, I thought of creating as section containing my obligations towards the viewers after reading Lauren Rosewarne’s book Periods in Pop Culture: Menstruation in Film and Television (2012) and Elizabeth Arveda Kissling’s On the Rag on Screen: Menarche in Film and Television (2002) on the representation of menstruation in screen. I realised that I was initially taking a damaging approach. When I looked back at my preparation material such as treatments and presentations, I can see a metaphorical and whimsical representation of blood. I chose stock photos of pads with red feathers or sequins instead of blood. I selected clips of pink dye falling in what looks like an aquarium. These showed up when I put the keyword menstruation in the search box of a stock photo provider. By misrepresenting blood, I was reinforcing the taboo. It was going against everything the film is about. I decided to research examples of the representation of menstruation specifically in non-fiction films. I made a video essay (2021). This work made me realise the power of showing blood as it is, in order to destigmatise it. This goes for any other elements characteristic of puberty.

Editing the film is our next step and it is often the stage of filmmaking where most ethical questions arise. Rebecca Barry explains this in her PhD thesis about the making of her documentary I am a Girl (2013):

Editor Lindi Harrison and I would discuss the ethical ramifications of including certain material. In the flurry of activity of filming on location it can be difficult to make decisions on the fly. However, back in the edit suite there is time to ruminate and dive deeper into ethical decisions. (2021, p.119)

I am looking forward to that process. I cannot wait to show Leonore what we have created together. It will have its challenges like the day Leonore told me that I cannot include clips where she’s crying. We had a discussion analysing books she reads, films or series she watches. She came to the conclusion that no story she has watched or read is a slide-show of good moments. She understood that tough times need to be part of the story to make it interesting. I know that I will have to lead by example trying to refrain from voicing self-criticism in the edit suite and accept that my triple chin goes in the cut.

Putting in place the processes I have learned along the way, successful or not, made me imagine tools that would have worked better during the making of this film but also potentially for other projects. I have listed my ideas in the conclusion below.

During the process of making First Blood [working title] I wondered if the protocol I developed would only be suited to the specific situation of directing a film with my family or whether it could be applied to another project. What this process showed me is that, as a filmmaker, I always put myself in the shoes of my participants. My baseline is: “don’t do anything you wouldn’t like to face yourself”. Therefore, this work will most likely be applicable to all my future projects.

The creation of the film’s protocol and the research that it entailed took an enormous amount of time which I will probably not have again on my next film. I therefore propose the creation of a new role: an ethics coordinator. I will discuss this recommendation in the next paragraph.

The help provided by Michela Carattini was key to a smooth filming process. She is a consent specialist with whom I could discuss all ethical aspects of the project, and she also acted as a neutral mediator between myself and Leonore. Therefore, I would like to recommend the creation of a new specialist role for the documentary industry: an ethics coordinator. This person could bring their ethical knowledge to the field and adapt their methods and protocols to the particulars of each documentary project. Instead of a rigid deontological code imposed on all non-fiction filmmakers, it would be a highly tailormade approach.

A new line on the budget is always a worry for documentarians but I would like to argue that investing in an ethics coordinator could spare the production time and money. With a more professional approach to informed consent, future issues could be mitigated. This person could detect problematic consent early in the project and avoid late defection or worse, a lawsuit. It would be presumptuous to think that an ethics coordinator would entirely prevent defections, but an open discussion led by a professional would identify potential problems early and offer a plan B.

For more vulnerable participants such as children, people from disadvantaged backgrounds or people with specific needs, an ethics coordinator could help obtain informed consent by taking the time to discuss the film’s goal with parents or guardians, as well as outlining any associated risks and their potential right of veto. Having a professional framework that protects participants, crew, and audiences could also help navigate or avoid any criticisms around the filmmaking process after the film is released.

I am not suggesting that documentary directors delegate the entirety of their relationship with their participants to an ethics coordinator, as it is critical that film directors maintain that connection. But, as mentioned in this exegesis, participants - especially children - are keen to please a director, creating a power imbalance which can undermine the process of securing informed consent. Having a neutral person act a mediator between the director and the participants, would make the filmmaking process a much more respectful and enjoyable one for everyone.

The ethics coordinator’s role would encompass five main duties: identify ethical risks for a specific project; organise individual one-on-one pre-consent consultations; help establish a protocol; plan a consent meeting with rushes review for each participant (with parents in case of a child); and finally, be available for a consultation in case a participant, crew member or the director needs additional advocacy or support.

This is a role that I would like to test out myself. My next step will be to identify and contact entities that educate on documentary ethics such as The Ethics Lab and see if they offer a training session I could attend. I could then offer my services to fellow documentarians and attempt to apply my learnings within the industry.

I have found that, due to the time constraints of a two-year master’s degree, one half-day class on ethics is insufficient to train future documentarians to at least ask themselves the key ethical questions. I therefore recommend that ethics takes up a proper module in documentary programs at film schools and is also offered as a dedicated short course for filmmakers already working in the industry. The module could include theoretical considerations and practical consent exercises.

I suggest that both fiction and documentary films are subjected to the same rules issued by The Office of The Children’s Guardian.

Of course, there is no such thing as a perfect film or a perfectly ethical process, but I have done my best effort to make a film in which process and consent were as fair as possible to Leonore, the other participants, and myself. My collaboration with Michela Carattini, our work on the film’s protocol, and my research, have allowed me to feel good about my work and, most importantly, resulted in an enriched relationship with my daughter. Now, I hope that by sharing my findings in this exegesis, I can help other filmmakers create their own ethical protocol and make their filmmaking experience a much more fulfilling and respectful one.

NOTES:

* The term women is used here in reference to humans who experience menstruation.

** AFTRS is the Australian Film Television and Radio School where I studied a Master of Arts Screen Documentary in 2021 and 2022.

Please find the bibliography HERE.

MEAA Journalist Code of Ethics

Indigenous Pathways and Protocols checklist (Janke 2009)

Transcript of interview with Rebecca Barry

Interview email to Maya Newell

See ideas of further research in HERE.